BREATHING THROUGH GRIEF

|

This is my dog Ramona. Yesterday morning she died in my arms. Events leading up to her death are too raw for me to share, but suffice it to say that I am shattered.

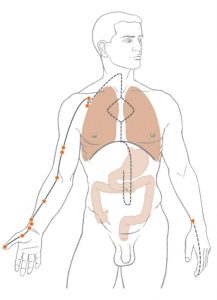

This morning I awoke feeling the way I did prior to my recovery from fibromyalgia — I hurt everywhere but had a particularly deep, sick ache in my chest, my inner forearms, and my hands. Laying in bed this morning I felt afraid. I declared victory over fibromyalgia years ago and had not felt this way in a long time. I asked myself — what on earth did I do to strain these muscles? Did I carry something heavy? Overuse my hands massaging a patient? Sleep in an awkward position? (No matter how many times as I advise my patients to look for a psychological rather than a physical cause for their pain, so often my first impulse is still to look for a physical explanation myself.)

I laid there with tears sliding down my face, thinking of Ramona, feeling my body hurt, and feeling frightened of my pain. Then the growing lump in my chest drew my attention to my breathing and that’s when it dawned on me: I wasn’t breathing in an attempt to keep my grief from crashing over me and carrying me away.

If there is no free flow, there is pain; if there is free flow, there is no pain

Everyone knows that the heart is the pump behind the circulation of the blood. But Chinese medicine teaches that the lungs — and the respiratory mechanism — are the pump behind the circulation of Qi. The ancient text upon which Chinese medicine is based (written around 200 BCE) says “bu tong ze tong, tong ze bu tong” which translates roughly to “if there is no free flow, there is pain; if there is free flow, there is no pain”. The ancient sages of Chinese medicine also taught that strong emotions — appropriately felt and expressed — also move Qi and that each organ resonates with a particular emotion. The emotion associated with the lungs is grief.

Of course we cannot completely stop breathing. We can, however, suppress or restrict our respiration. This reduces our overall energy level and hence limits the energy available for feeling. Without consciously recognizing what we were doing, almost all of us learned at a very young age to restrict our breathing in order to control the intensity of our emotions. Perhaps as a child we were humiliated, criticized, or punished for having shown emotion and from that point in time onward we vowed not to cry. We learned that if we hold our breath, feelings do not hurt as much, it is easier to bite our tongue, and tears are less likely to overtake us. This is such an effective technique that it becomes a habit and by the time we reach adulthood we don’t know what it feels like to breathe normally.

Letting go

The function of the lungs is to let go so that we can take in. The lungs close in order to expel carbon dioxide before they can open in order to receive oxygen. On an emotional and spiritual level, the lungs enable us release old ideas, relationships, and experiences in order to make space to receive new ones. The taoists recognized that change is a universal law — nothing lasts forever. Summer gives way to winter, growth gives way to decay, birth gives way to death. There are hellos and goodbyes, meetings and partings. No matter how much we love someone or something, we cannot hold onto anyone or anything forever.

Breathing through my grief

And so I consciously let go. I deliberately unclenched my hands, relaxed my jaws, softened my arms. I took a deep breath and, as air filled my chest, I felt the agony of grief wash over me. As I breathed, sobs and then groans of anguish erupted through the lump in my throat. I felt the impulse — almost a reflex — to close down because it hurt so much. But I kept breathing and the grief kept coming, until it felt like waves crashing over me. I kept breathing, even when it felt like my sorrow was about to carry me out to sea. My husband held me and I cried. And I breathed. And I breathed. And as I breathed I let go a little bit more. Eventually the lump in my throat released and my tears stopped. I kept breathing and realized that, although my heart was still broken, my body didn’t hurt.

“Coping requires that we repress emotions that might interfere with whatever we are trying to do and TMS exists in order to maintain repression of those emotions.”

– John E. Sarno, MD, Healing Back Pain

That is when I realized that there is no such thing as “final” victory over TMS and chronic pain. When I claimed that a couple of years ago I was a bit naive. No life is free of emotional pain, loss, and heartbreak and each time difficult emotions arise we are faced with a choice: do we stop breathing (figuratively or literally) in order to make our feelings manageable in the short term (and risk physical pain taking hold in order to maintain that repression), or do we surrender to our heartbreak, feel our way through, ugly cry when the need arises, and then then eventually emerge, integrated and whole?